Paths of Preservation

Exploring how projects across different scales and regions redefine urban ecological restoration and social inclusion, Paths of Preservation invites reflection on the intersection of biodiversity, equity, and design—and on how these lessons can shape our practice as designers and planners.

The MKSK Trek Fellowship is a funded travel and research program open to MKSK professionals to explore critical issues in design, landscape, planning, and urbanism.

Objectives of the Research

This Trek seeks to spark a broader conversation and introduce a framework toolkit that could help professionals and communities shape environments where people and nature thrive together.

Paths of Preservation is rooted in the belief that landscape architecture can be both a tool for ecological repair and a platform for social empowerment. The mission centers on documenting and translating Costa Rica’s unique model of stewardship where communities, designers, and ecosystems work together in actionable strategies that strengthen climate resilience, biodiversity, and equity.

The vision looks ahead to a future in which these lessons inspire global practice and where cities and ecosystems are intentionally co-designed as interconnected systems of care, education, and resilience.

Paths of Preservation imagines a world in which design is not merely reactive, but regenerative; where every corridor, park, and wetland serves as both habitat and home; and where shared stewardship cultivates a culture of preservation that transcends borders.

Mission

This Trek aims to document, interpret, and translate Costa Rica’s model of ecological stewardship and community-driven design into actionable strategies for landscape architecture. Through on-the-ground research and collaboration with local practitioners, this Trek highlights how conservation, climate resilience, and social equity intersect across urban and natural landscapes. The mission is to spark a conversation and think about a framework + design toolkit that empowers professionals and communities alike to shape environments where biodiversity and people thrive together.

Vision

To envision a future where the lessons of Costa Rica’s landscapes and other replicable models inspire global practice, and where cities and ecosystems are co-designed as interconnected systems of care, education, and resilience. Paths of Preservation imagines a practice in which design is not only a response to ecological loss but a catalyst for regeneration; where every park, wetland, and green corridor serves as both habitat and home, advancing a shared culture of preservation.

Costa Rica has emerged as a global leader in harmonizing ecological preservation with socially inclusive urban development. This presentation documents an immersive research journey that explores how landscape architecture and urban design can simultaneously address biodiversity loss, climate change, and systemic environmental injustice.

By studying a wide range of urban ecological interventions, conservation programs, and inclusive public space designs, this project offers a deep dive into Costa Rica’s multi-scalar response to planetary and societal challenges.

The purpose of this research is to demonstrate that nature-based solutions are not only environmentally necessary but also socially transformative. Landscape architecture can be a tool to reconcile people with nature, creating regenerative systems that serve both ecological and cultural functions. Costa Rica offers tangible examples of how design can nurture biodiversity, protect vulnerable communities, and foster civic pride.

Through direct site observations, interviews, and photographic documentation, this research highlights strategies that advance resilient cities while centering equity. Each site reflects a different scale and strategy, from expansive national parks to intimate urban interventions. Together, they form a holistic understanding of what inclusive environmental design can look like in practice.

What if Costa Rica was not an exception..... but the blueprint?

Restore urban waterways as ecological and social arteries.

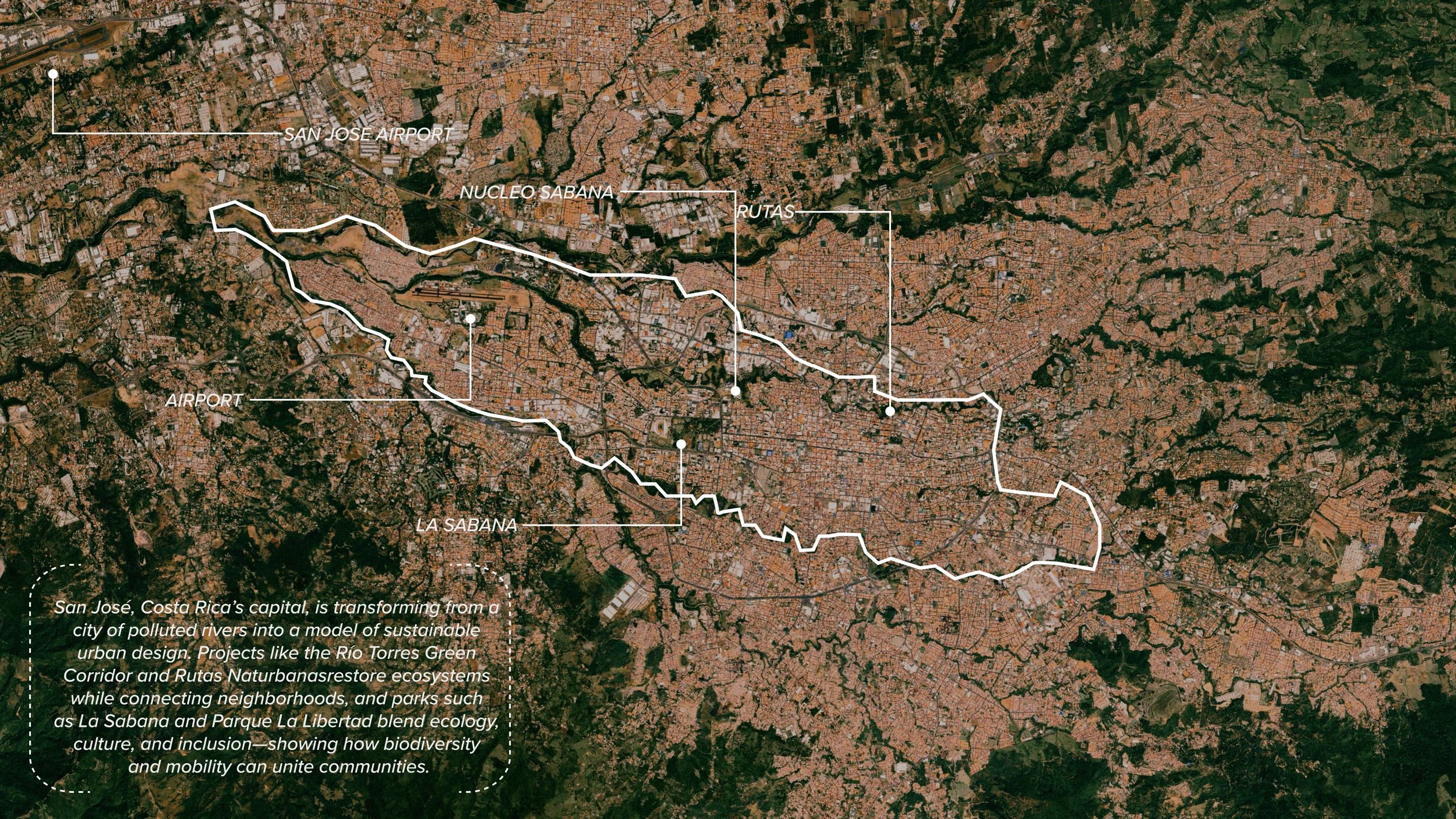

San José: Urban Regeneration and Ecological Connectivity

We start at San José, Costa Rica’s capital. It embodies the country’s evolving balance between ecological policy and rapid urbanization. Once marked by disconnected green spaces and polluted rivers, the city is now a proving ground for equitable urban transformation. Projects like the Río Torres Green Corridor and Rutas Naturbanas restore ecosystems while creating inclusive public spaces that connect over 30 neighborhoods. Parks such as La Sabana and Parque La Libertad model how environmental education, accessibility, and cultural programming can coexist.

San José demonstrates how biodiversity, mobility, and civic identity intertwine—transforming ecological corridors into social infrastructure that unites communities through design.

Empower neighborhoods through spaces that merge ecology, education, and culture.

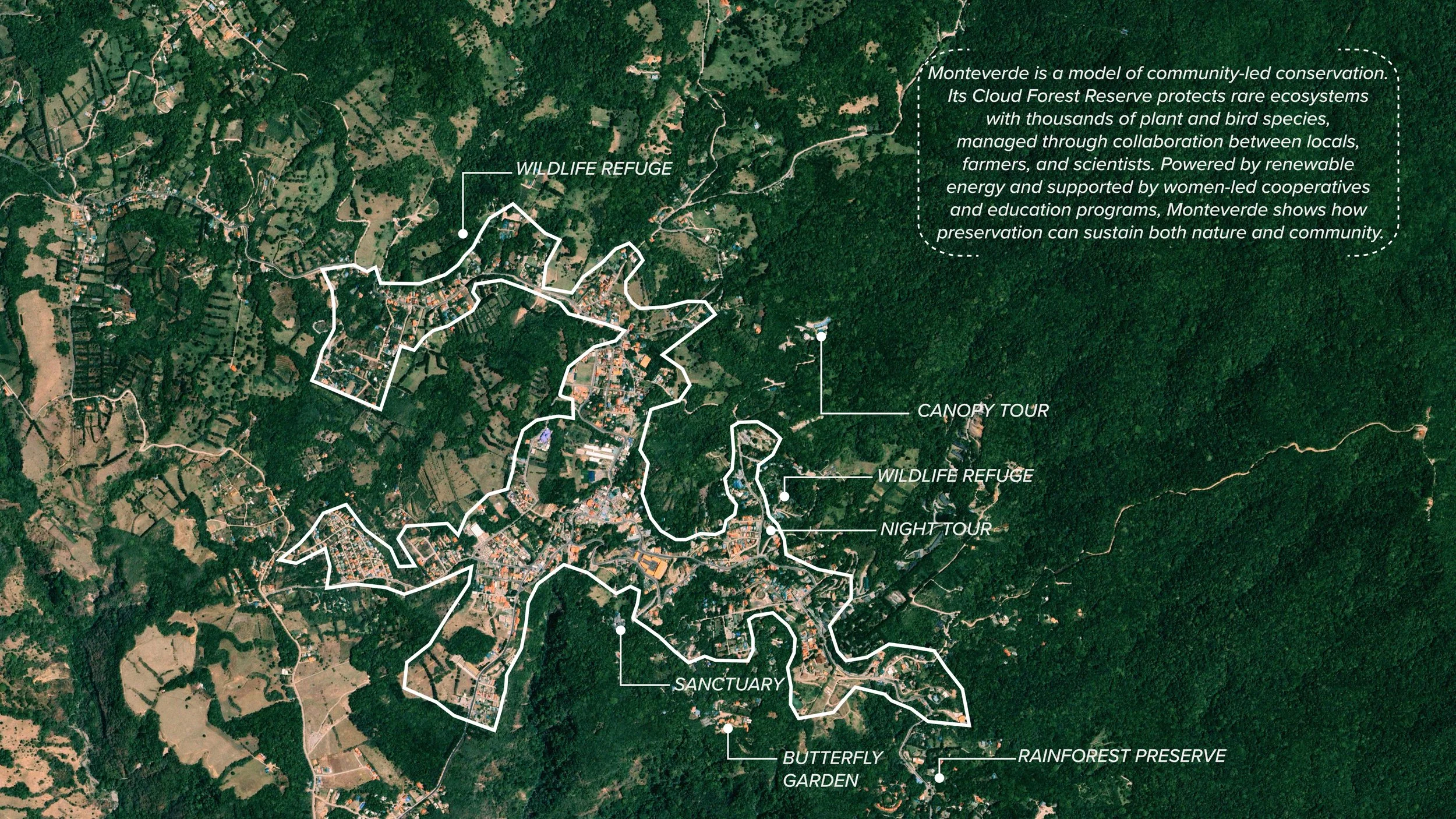

Monteverde: Cloud Forest Conservation and Environmental Education

Our journey then takes us to the mist-covered Tilarán Mountains in Monteverde. Monteverde stands as one of the world’s most successful community-based conservation stories. The Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve protects rare ecosystems dependent on stable microclimates, harboring over 2,500 plant species, 400 birds, and countless endemic insects. The area’s conservation success is anchored in local collaboration among residents, farmers, and scientists who co-manage forests and ecotourism enterprises.

Monteverde’s model links ecological preservation with education and equity through sustainable tourism, women-led cooperatives, habitat research, and reinforcing the forest as both classroom and livelihood.

Blend storytelling, ecology, and community heritage.

Osa Peninsula: The Last Great Wilderness

We then head south about 250 miles to reach The Osa Peninsula. This region represents the biological core of Costa Rica’s natural heritage housing 2.5% of Earth’s biodiversity within a single region. Its rainforest, mangrove, and coastal ecosystems are carbon powerhouses, storing ~50 tons of carbon per hectare, among the highest globally. Community initiatives support sustainable forestry, native species nurseries, and wildlife monitoring programs led by local residents.

Costa Rica’s capital region faces a series of urgent environmental and public-health challenges that shape everyday life for its residents. In some parts, forest cover has dropped to 0%, eliminating the natural cooling, biodiversity support, and climate resilience that tree canopies provide. At the same time, toxic air particles exceed permitted levels by 70–80% in the central district, amplifying respiratory health risks.

Mobility also plays a major role: traffic congestion consumes 6.5% of the national GDP, reflecting both economic loss and daily stress for commuters. Water quality paints an even more severe picture—Río Torres contains 617 million fecal coliforms, vastly above the safe threshold of 1,000, signaling extreme contamination of one of the city’s primary waterways. These pressures converge with road safety concerns, as traffic accidents remain the third leading cause of death nationwide. Altogether, these indicators reveal how deeply environmental decline is intertwined with public health, mobility inequity, and ecosystem loss in San José.

San Jose, Costa Rica. View from Nucleo Sabana.

Across the Greater Metropolitan Area (GAM), environmental degradation is reshaping ecological patterns in ways that directly impact urban communities. Only 12% of native bird species still nest in the urban core due to habitat fragmentation and the disappearance of vegetation. This is a signal of a rapidly shrinking ecological corridor system.

This loss of tree canopy also intensifies climate impacts: urban heat islands in San José can reach temperatures 4–6°F hotter in neighborhoods with less than 10% canopy cover, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations.

The city’s waterways tell a similar story—40% of streams have lost continuous biological corridors, limiting movement for small mammals, amphibians, and pollinators essential to ecosystem health. Even in public spaces, biodiversity is underrepresented: less than 5% of parks include pollinator-friendly plantings, despite Costa Rica being home to more than 650 bee species. This slide underscores how biodiversity loss, extreme heat, and fragmented ecosystems are eroding the country’s environmental resilience.

Monteverde, Costa Rica. View of Santa Elena.

Environmental vulnerability in Costa Rica is deeply connected to social and spatial inequities. Over 70% of informal settlements are located near contaminated rivers, placing thousands of families in daily proximity to polluted water that fails national health standards. Air pollution is similarly uneven—communities located along major transportation corridors face 30–50% higher exposure than the rest of the city.

Climate impacts compound these risks: low-income neighborhoods experience 2–3× higher flood frequency due to inadequate drainage infrastructure and limited green space, creating cycles of recurring damage. Meanwhile, access to quality parks and green public space varies dramatically, by up to fourfold, between more affluent districts and densely populated areas with little room for recreation or ecological refuge. This slide highlights how environmental injustice shapes who benefits from nature—and who bears the environmental burden.

Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica. View of Drake Bay.

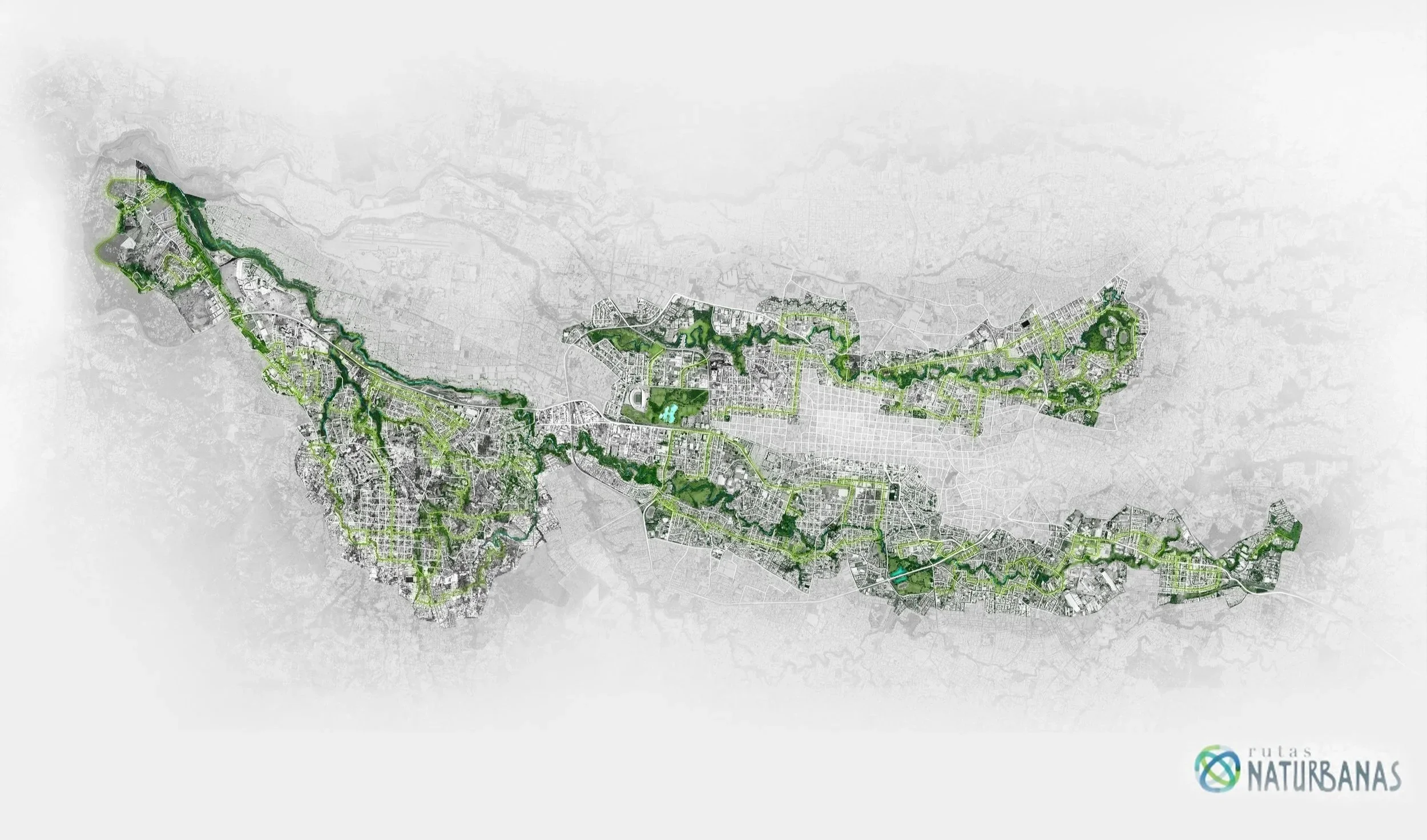

San Jose

Image Credit: Rutas Naturbanas

Rutas Naturbanas is one of Costa Rica’s most visionary urban ecological initiatives. It is an expansive, citywide network designed to heal rivers, reconnect communities, and embed nature back into the urban core of San José. At its heart, the project reimagines the metropolitan river system as a continuous ecological and public mobility corridor, linking neighborhoods through restored landscapes that were once polluted, fenced, or forgotten.

Stretching across key watersheds including Río Torres, Río Agres, and the major civic anchors of La Sabana and Núcleo Sabana, Rutas Naturbanas integrates native reforestation, habitat restoration, public trails, interpretive spaces, and equitable access to recreation.

The initiative is built not only as a physical network, but as a social and environmental platform: one that fosters conservation, community stewardship, and climate resilience within an increasingly dense urban region. Its purpose is to clean waterways, reintroduce biodiversity, create safe walking and biking routes, and expand access to green spaces for the nearly two million residents of the Greater Metropolitan Area.

What sets Rutas Naturbanas apart is its collaborative governance model. Communities, NGOs, universities, and public institutions co-manage sections of the corridor, ensuring that the transformation is rooted in local identity and shared responsibility. This approach allows ecological restoration to unfold alongside cultural activation, environmental education, and neighborhood-led stewardship.

Ultimately, Rutas Naturbanas demonstrates how a city can center its recovery around its rivers treating waterways not as obstacles or invisible edges, but as living infrastructures that support biodiversity, mobility, and social well-being. By restoring the natural arteries of San José, the initiative reframes what urban resilience can look like: a city where ecology and community thrive together, where rivers become connectors rather than dividers, and where green networks form the backbone of an inclusive, sustainable future.

Monteverde

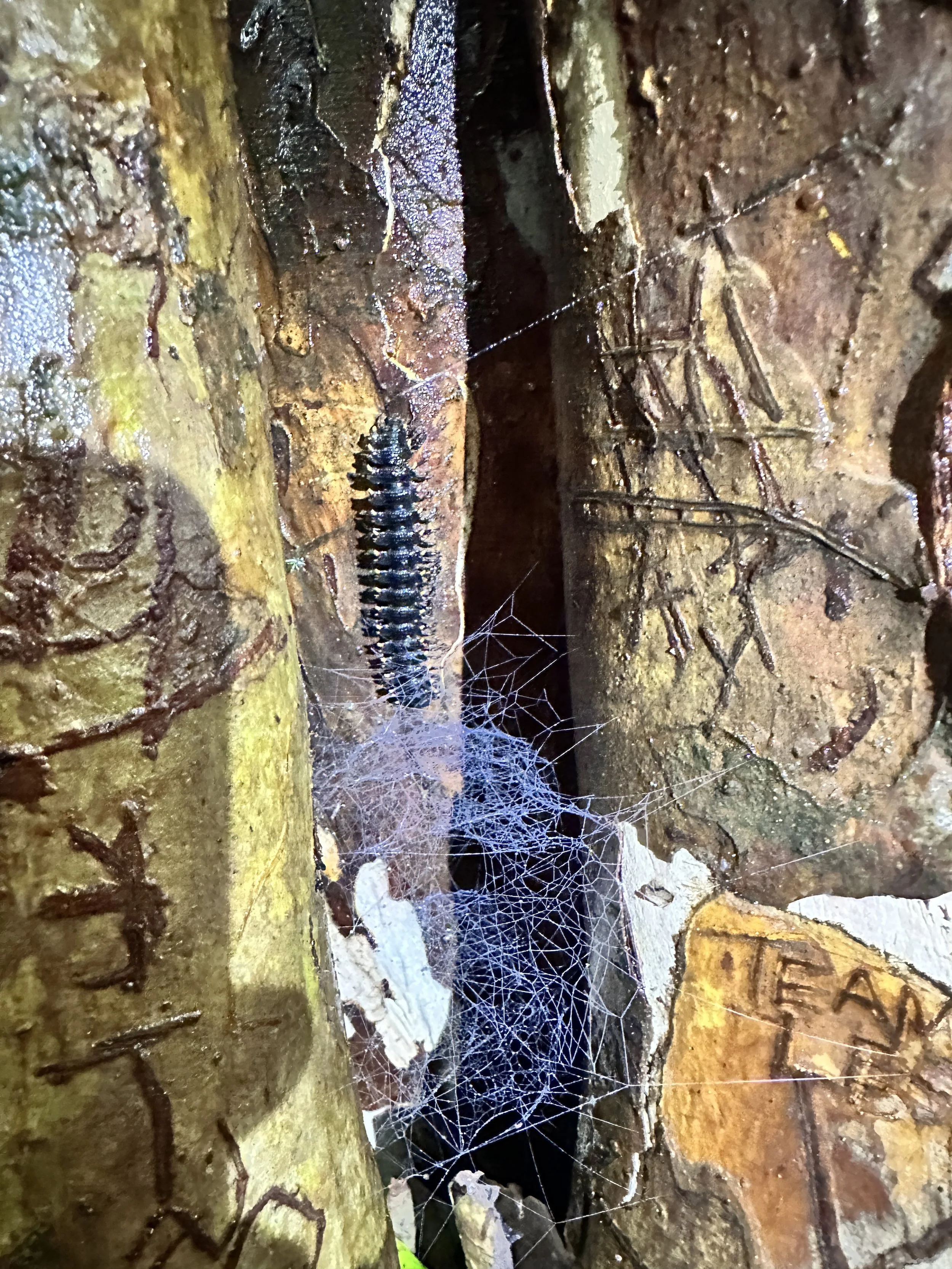

As the drone view pans over Monteverde, the landscape reveals a rare typology where community and cloud forest are seamlessly intertwined. From above, eco-lodges, homes, farms, and footpaths disappear into the canopy, demonstrating a model of development that grows with nature rather than against it. This aerial perspective shows how Monteverde’s built environment is intentionally low-impact scaled, sited, and designed to disappear into mist-fed forests that sustain thousands of species.

The result is a community where daily life unfolds within an ecological sanctuary, setting the stage for understanding the region’s extraordinary biodiversity, conservation practices, and culture of coexistence. With this context, we will next explore the species, habitats, and preservation systems that make Monteverde one of the world’s most important living laboratories

Monteverde offers one of the clearest examples of how conservation, community, and everyday life can coexist within a shared landscape. Its patchwork of refuges, sanctuaries, canopy tours, farms, and research centers forms a living network of protected spaces woven directly into the town’s fabric. From women-led cooperatives to family-run eco-lodges, Monteverde’s preservation model is built on local stewardship, environmental education, and renewable energy systems that sustain both people and ecosystems. Here, neighborhoods are not separated from nature. They are surrounded by it, shaped by it, and responsible for it.

Osa Peninsula

The Osa Peninsula represents one of Costa Rica’s most extraordinary examples of how biodiversity, community heritage, and ecological stewardship intertwine across a shared landscape. Containing an estimated 2.5% of all species on Earth within a single region, Osa’s rainforests, mangroves, marine ecosystems, and protected areas such as Corcovado National Park and Caño Island function as one continuous ecological network.

These habitats act as powerful carbon sinks storing up to 50 tons of carbon per hectare while community-led programs in sustainable forestry, mangrove restoration, eco-tourism, and wildlife monitoring ensure that conservation supports local livelihoods. Here, storytelling, tradition, and environmental knowledge are passed across generations, shaping a culture where people and nature depend on one another.

As a living model of climate resilience and community stewardship, the Osa Peninsula offers critical lessons for Paths of Preservation, demonstrating how conservation succeeds when ecosystems and communities are protected and empowered together.

From above, Drake Bay reveals the remarkable intersection of forest, coastline, and community—an ecological threshold where preservation, livelihoods, and biodiversity all meet. The aerial view captures one of Central America’s richest biological corridors, where rainforest, river systems, and the Pacific Ocean merge to support species found nowhere else on Earth.

Here, small communities steward vast ecosystems through environmental education, reef and forest restoration, and eco-tourism that sustains local livelihoods. Drake Bay shows how conservation gains strength when the community, the coastline, and the forest function as one interconnected system—each one shaping and sustaining the other.

Building on MKSK’s foundation, we can expand the carbon sequestration toolkit to address broader ecological and social priorities. What if it included biodiversity support, watershed repair, community education, and equitable access to nature? By integrating these typologies into multi-program public spaces, cultural destinations, and mobility corridors, we move from isolated interventions to a cohesive green network that strengthens resilience across entire cities and regions.

Community

Hubs

Inspired by: Parque La Libertad and La Sabana in San Jose

Key Goal: Turn underused land into multi-program public campuses.

Benefits:

Provides equitable access to green space and civic resources.

Builds environmental literacy through arts, workshops, and youth programs. Generates community-led maintenance and ownership.

Where Can Community Hubs Be Implemented?

Vacant lots

School campuses

Neighborhood parks

Interpretive Landscapes

Inspired by: Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve + Caño Island

Key Goal: Use design to educate visitors on biodiversity, conservation, and cultural values.

Benefits:

Builds public understanding of ecological processes. Honors indigenous and local heritage.

Strengthens community connection to conservation goals.

Where Can Interpretive Landscapes Be Implemented?

Visitor centers

Waterfront promenades

School or museum grounds

River

Corridors

Inspired by: Río Torres Green Corridor + Rutas Naturbanas

Key Goal: Reconnect fragmented riparian systems through multi-use greenways.

Benefits:

Improves stormwater management and flood resilience.

Expands habitat corridors for wildlife.

Connects communities through equitable green mobility networks.

Where Can River Corridors Be Implemented?

Urban riverfronts

Greenway retrofits

Industrial-to-park conversions

Neighborhood stormwater routes

After this research, there is another important question we should ask ourselves and spread to other practitioners:

What if we designed like our future depends on it .....because… this is not just a case study, but a call to action. When we design with nature and people at the center, we build more than place; we build resilience.

The ASLA Climate & Biodiversity Action Plan reinforces that landscape architects, planners, and urban designers play a central role in shaping resilient, equitable, and low-carbon communities. As climate impacts accelerate and biodiversity declines, our professions are uniquely positioned to design systems that repair ecosystems while improving human well-being.

This work is not optional, but a professional responsibility. The Action Plan calls on us to restore landscapes, expand nature-based solutions, and create public spaces that reduce emissions, cool cities, capture carbon, and strengthen habitat connectivity. It also charges us with advancing environmental justice by ensuring that vulnerable communities receive the benefits of climate adaptation and green infrastructure.

By integrating ecological restoration, community engagement, and climate-positive design across every project and every scale we help cities transition toward a regenerative future. The tools, strategies, and precedents presented here today echo the core goals of the Action Plan: to protect biodiversity, heal broken systems, and design places where people and nature thrive together.

This work defines the future of our profession. It positions us as leaders in the global movement to address climate change, restore ecological health, and build more just, livable communities across different scales.

Special Thanks To

Dana Viquez Azofeifa, José Vargas Hidalgo and PPAR team for welcoming, informing, and offering their time and resources.

Alonso Briceño RodrÍguez and Carlos Velásquez Ortiz for their interview time and resources.

Javier Ortiz is a Landscape and Urban Designer at MKSK. He strives to create designs that promote healthy living, ecological resilience, and social interaction. Javier is an advocate for excellence in community and stakeholder engagement. With his experience in Chicago and New York, Javier brings particular interest addressing social and environmental justice through design and hopes to contribute to a more vibrant, equitable, and sustainable future for all. Being fluent in Spanish and English has allowed him to communicate effectively with diverse teams and clients. This bilingual proficiency has consistently enhanced collaboration by improving community understanding and supporting cross-cultural relationships between the client and the project team.