What Would A Woman-Made City Look Like?

Explore the gender equitable planning and design practices that an MKSK planner discovered on her recent travels in Sweden.

The MKSK Trek Fellowship is a funded travel and research program open to MKSK professionals to explore critical issues in design, landscape, planning, and urbanism.

What would cities and urban spaces look like if they were designed through a gender equitable lens? This is the main question that MKSK Associate and Planner, Sarah Lilly, investigated on her recent travels to Sweden through the Trek Fellowship program.

The Gendered City

Gender and its relationship to cities and urban spaces is a complex topic that began to emerge as a prominent topic of planning and design scholarship starting in the 1970s. As architect and urban historian, Dolores Hayden, put it:

“‘A woman’s place is in the home’ has been one of the most important principles of architectural design and urban planning in the United States for the last century.”

(Hayden, 1980)

This legacy of women’s relegation within the private or domestic sphere and men’s domination of the public sphere has had profound lingering effects on cities. While cultural norms and attitudes surrounding gender have changed dramatically over the last several decades, our cities and urban systems are slower to change. Therefore, this concept of the “gendered city” persists today and continues to reinforce larger gender inequities. Put concisely by geographer, Jane Darke:

“Our cities are patriarchy written in stone, brick, glass and concrete.” (Darke, 1996)

Due to the complex systems of our cities, the “gendered city” becomes a positive feedback loop, contributing to reduced access and freedom for women and gender marginalized people, continued social and economic exclusion, and a lack of agency and representation in planning and design processes. These factors continue to shape the “gendered city”, and the cycle continues.

A diagram illustrating a positive feedback loop between the “gendered city” and reduced access in the public sphere, social and economic exclusion, and a lack of agency and representation in planning and design

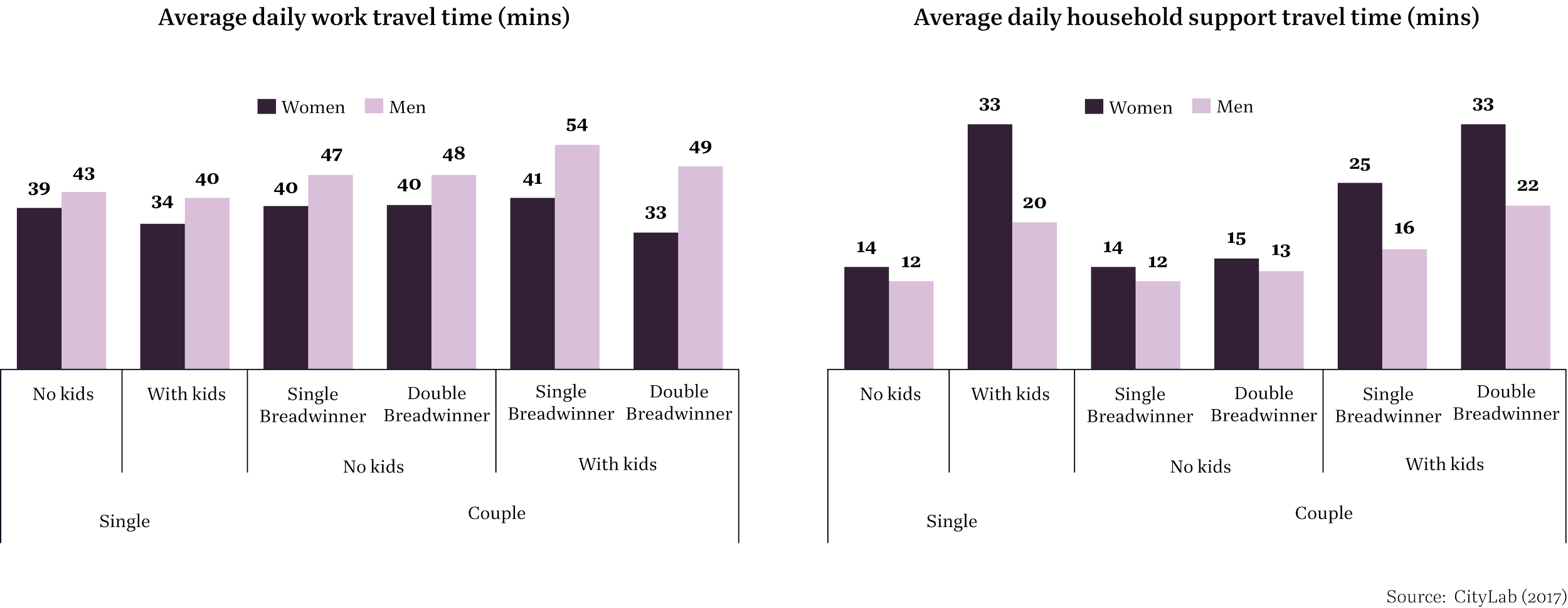

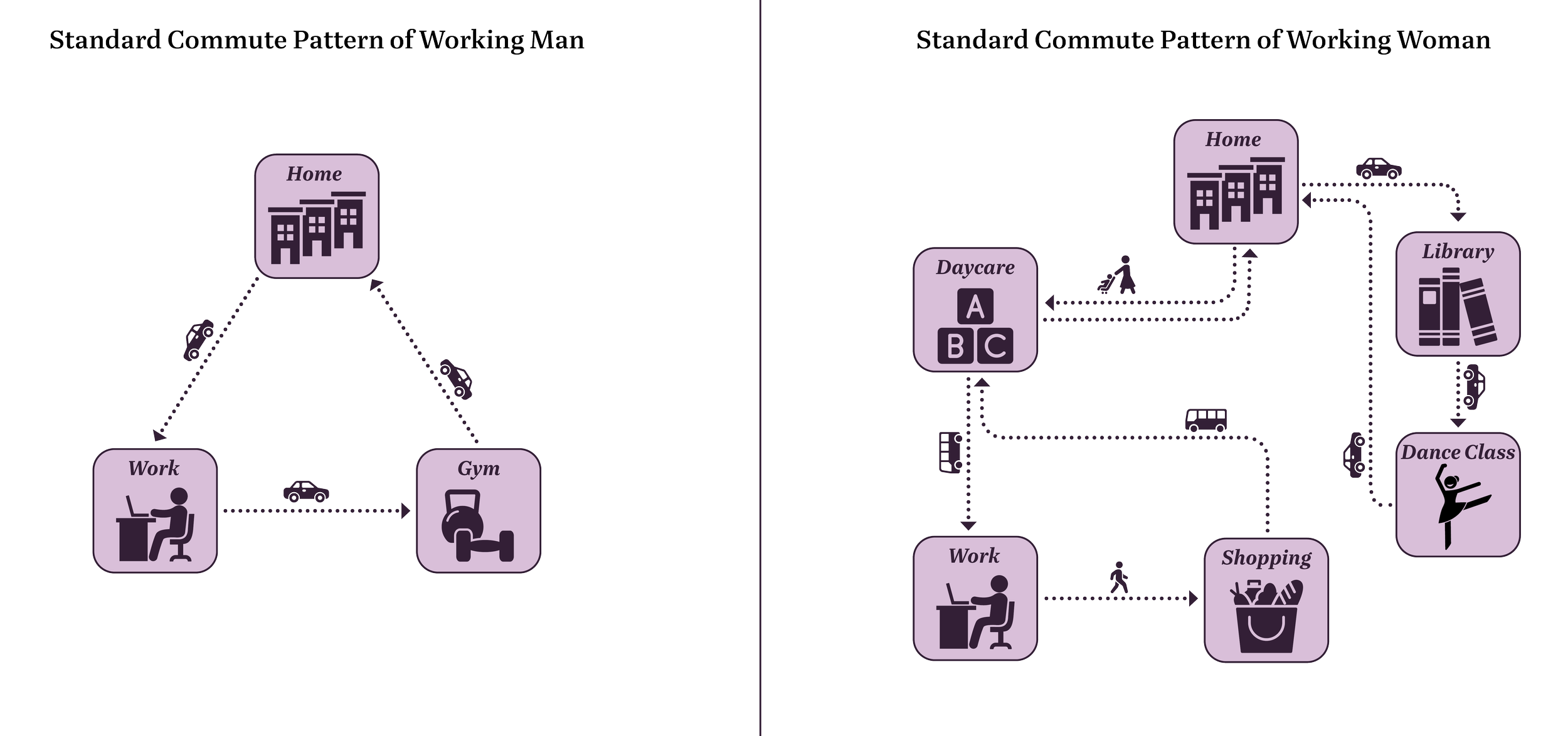

These dynamics play out in concrete ways that impact people’s quality of life. Take commuting patterns as an example. Across all types of households men spend more time than women commuting to work, while women spend more time than men commuting for household support. Not only are women traveling more for household support, but they also are more likely to make those trips on their commute to and from work, a pattern known as “trip chaining” (McGuckin and Nakamoto, 2004).

Urban mobility systems, however, are mostly designed around the idea that we need to move people as efficiently as possible to and from work. Neglecting these gendered differences in travel patterns means that women have reduced freedom of movement and access within cities.

Cities around the world, from Vienna to Los Angeles to Buenos Aires are starting to take note of these issues and working on solutions to become more gender equitable places. Sarah traveled to Sweden to visit Umeå, one such location that is setting the standard for what a gender equitable city looks like.

Lessons Learned from Umeå, Sweden

Heralded as one of the most feminist and gender equitable cities in the world, Umeå, Sweden was the primary destination for Sarah’s research. Located near the Arctic Circle, Umeå is a city of about 130,000 people with a college-town feel thanks to the presence of Umeå University, with a student population of nearly 38,000. Umeå has been working toward gender equity in policymaking and planning for many decades, being always at the forefront of progress. National and European policies do help to support and bolster local actions taken by municipalities in Sweden, like Umeå.

A timeline graphic showing key milestones for gender equity in Umeå and Sweden from 1909 to 2018.

To highlight its progress, Umeå has created a Gendered Landscape tour, which Sarah embarked on during her travels. Below are three sites that she encountered during her time in Umeå that provide an example of what cities could look like if designed through a gender equitable lens.

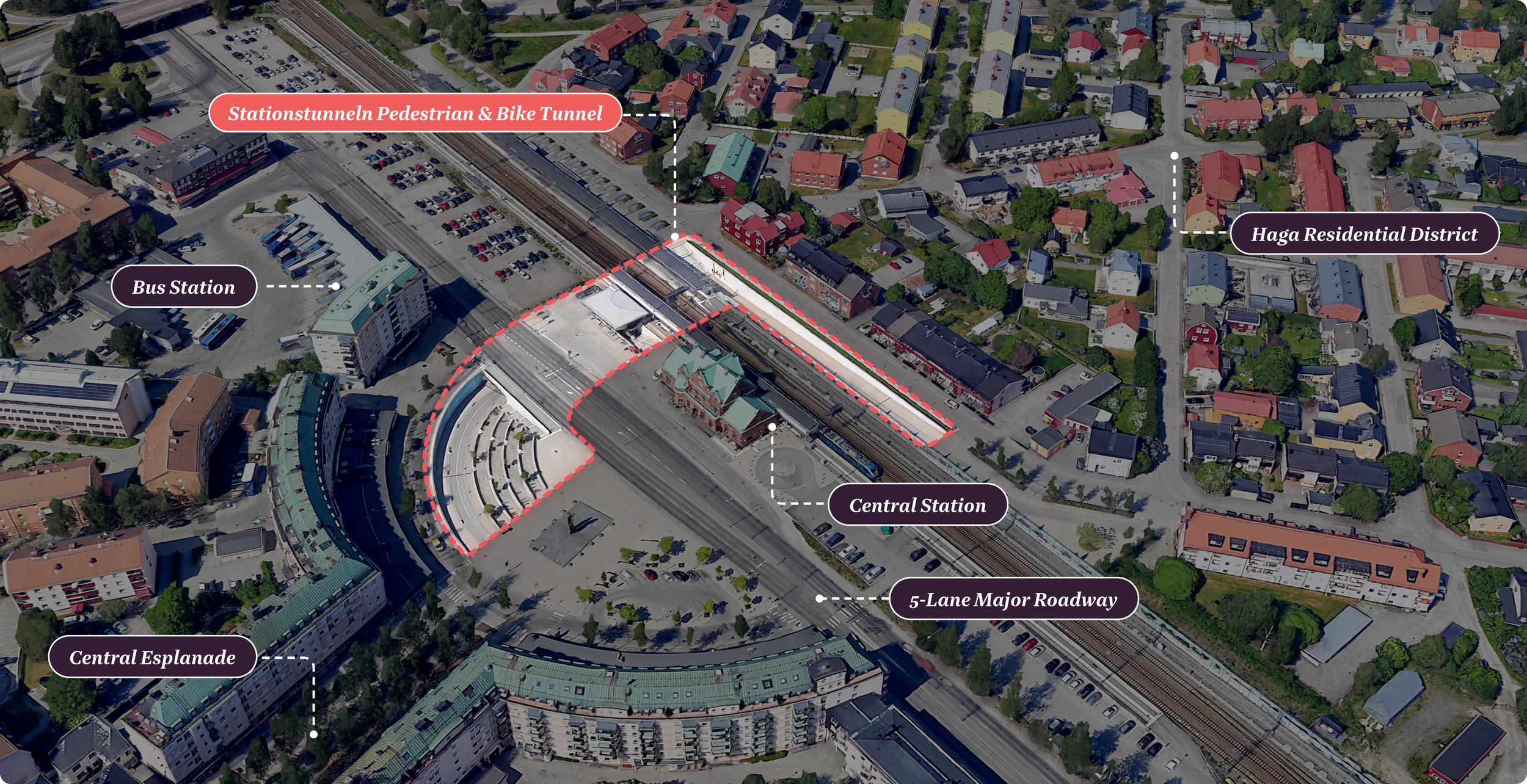

Stationstunneln or Station Tunnel

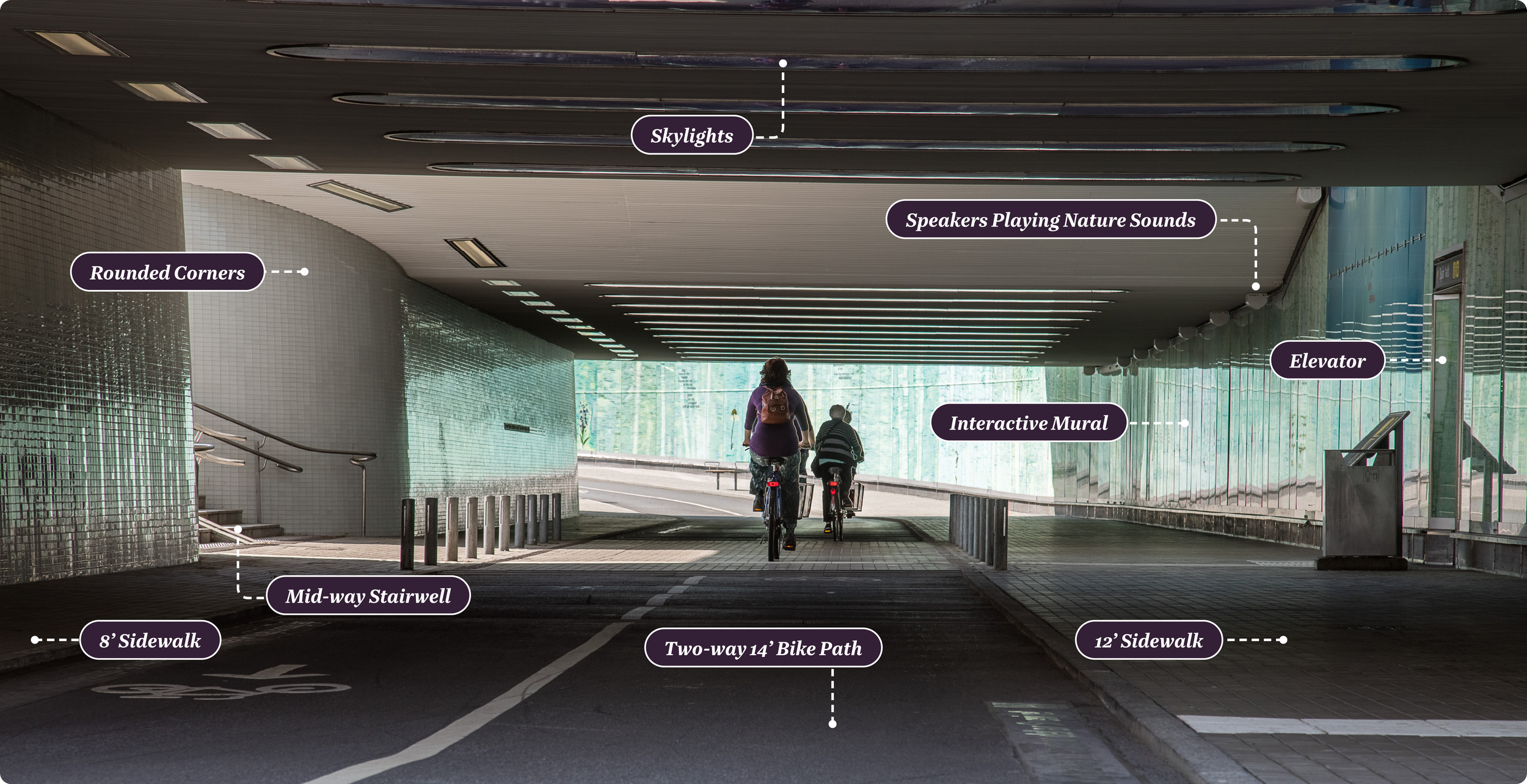

Research shows that women frequently experience stranger harassment and sexual harassment in public space, which has severe negative consequences for their well-being and contribute to their freedom of movement in cities (Fairchild and Rudman, 2008). To address these issues, this pedestrian and bike tunnel under Umeå’s central train station was redesigned specifically with women’s safety in mind. From a narrow and dark underpass, the tunnel was transformed into a bright, open, and welcoming space that not only serves as a passageway, but a destination.

The design prioritizes rounded corners and wide-open entrances to maximize visibility and natural light filtration. A mid-way stairwell provides access to the train platforms as well as a quick exit point, if needed. Double handrails and a pram ramp on the stairwell make traveling to this space with children much more accessible. A glass mural along the tunnel celebrates the work of Sara Lidman, a local author whose voice can be heard through button-activated audio samples of her work. Because of the unique features of this tunnel, it attracts people who are not only traveling through, but traveling to the space, furthering the sense of safety through passive surveillance.

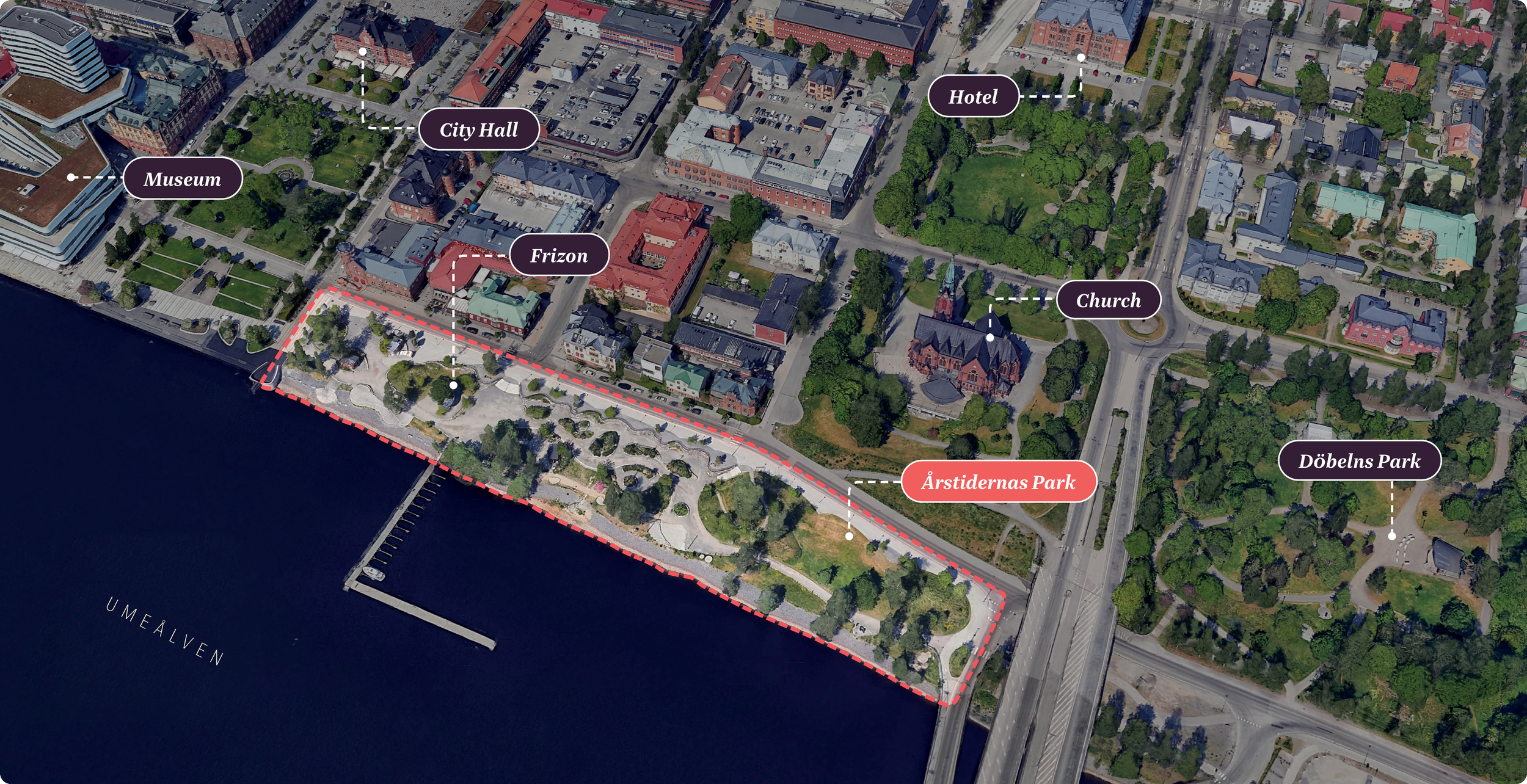

Frizon or Free Zone in Årstidernas Park

Nestled into a park along the Ume River, the Frizon, or “free zone” is a space designed by and for teen girls. Research shows that teen girls frequent parks less than teen boys (Evanson et al, 2018), which can be at least partially attributed to a lack of facilities within parks that cater to the needs of teen girls. Research points to teen girls’ desire for seating which allows face-to-face socialization, swings, smaller “rooms” within parks so different groups can share the space, walking paths, public restrooms, and recreation equipment that is comfortable for them to use (Walker and Clark, 2023).

This dynamic was also the case in Umeå, so the municipality and the design team held workshops and charrettes with local teen girls to arrive at the design for the Frizon. The social seating structure features circular swinging benches, that are ergonomically designed to the average teen girl specifications, a center “stage” for creative play, ample lighting designed into furnishings, and even built-in Bluetooth speakers for playing music.

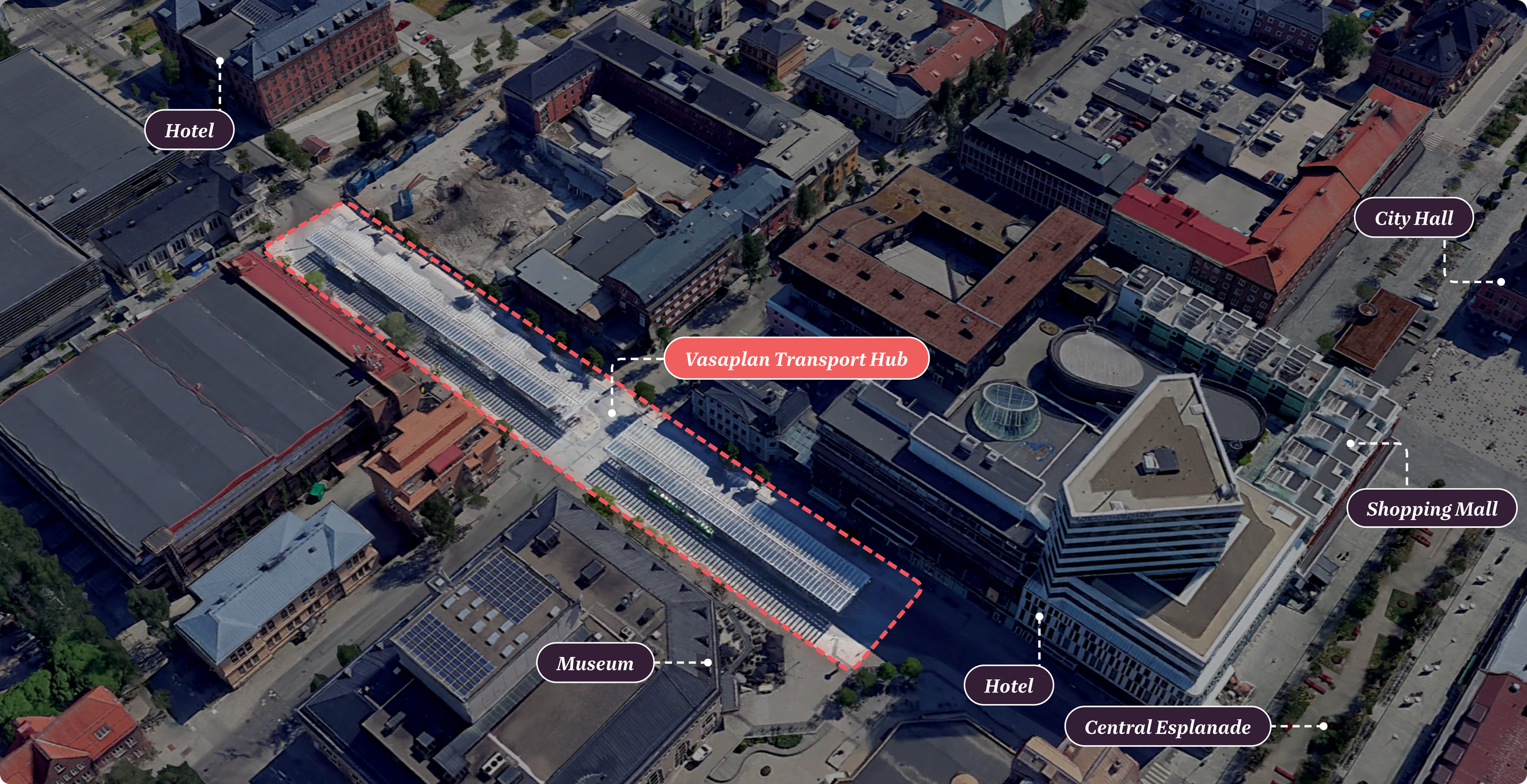

Vasaplan Transportation Hub

Globally, women are more likely than men to walk or take public transportation, often out of necessity due to care responsibilities, reduced access to a personal vehicle, and less disposable income (Kurshitashvili et al, 2022). In traveling via these modes of transportation, however, they often experience sexual violence and harassment, making the journey a fear-inducing one (Ison et al, 2023).

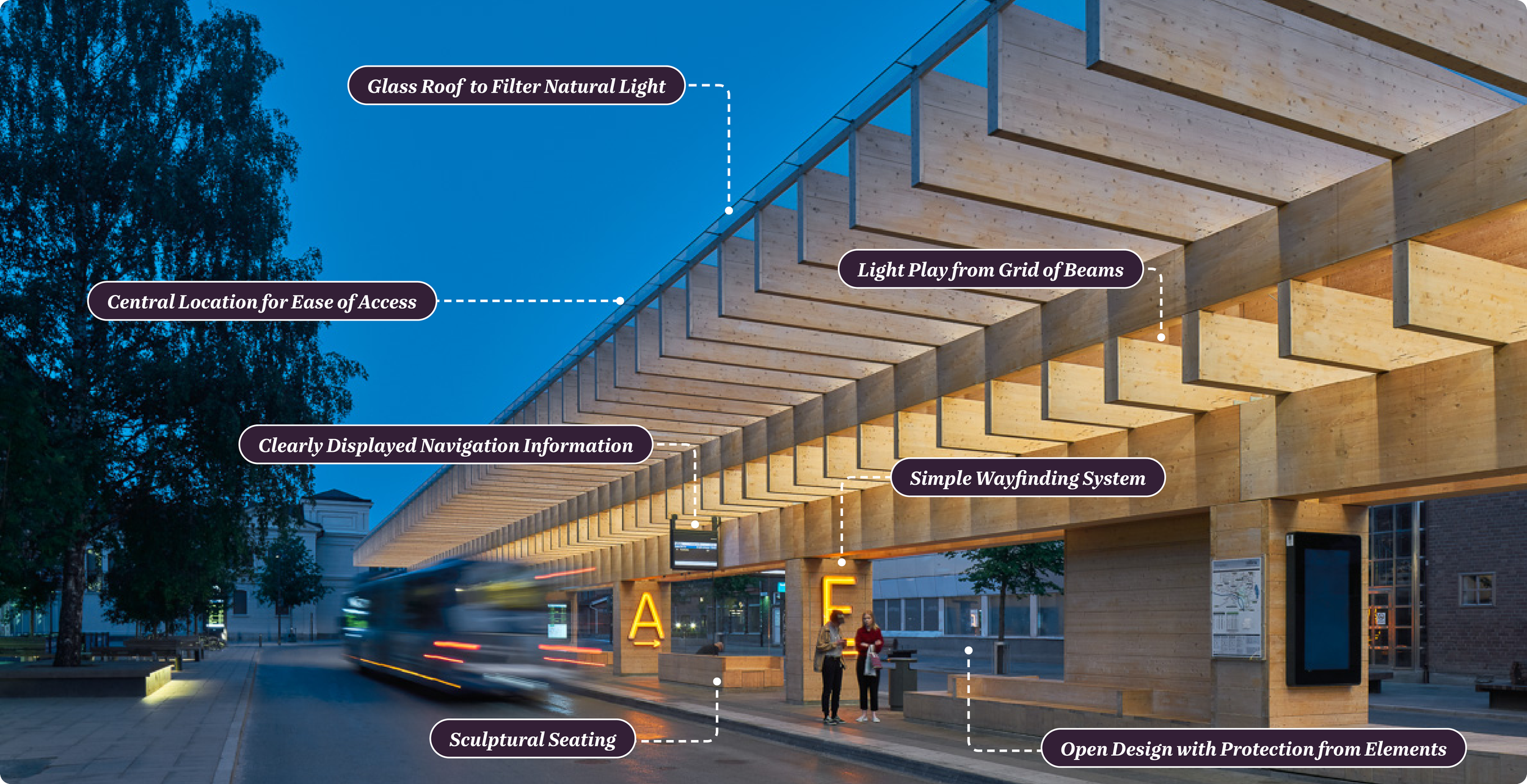

Umeå’s centrally located Vasaplan transport hub, while technically not part of the Gendered Landscape tour, was an impressive example of an urban bus terminal. Spanning a street median along two city blocks, the structure is the city’s main local transportation hub, where multiple bus routes converge. The terminal design is light and open, with a grid of local timber beams capped by a glass roof. The simple and graphic wayfinding system and digital displays make navigation extremely accessible.

The bus system that utilizes stations like this one is also planned through a gender equitable lens, with routes that provide access to all residential districts within the city and ample stops located around the university hospital, the largest employer of women in the city.

Key Takeaways

From the experiences in Umeå, Sarah arrived at a few overarching takeaways that planners and designers should consider to create more gender equitable cities.

Understanding Diverse Lived Experiences

First, to truly plan and design equitable places, it is critical to understand the differences in people’s lived experiences. People often have vastly different lived experiences in urban places based on their gender and other intersecting identities like age, race, disability, and more. Understanding the reality for different populations of people allows planners, policymakers, and designers to tailor decisions to their diverse communities.

Planning & Designing for Caretaking

In most societies, Sweden included, women spend more time than men on caretaking and household tasks. Due to the legacy of men’s domination of the public sphere, the infrastructure for caretaking has often been neglected in cities. This includes elements like pram/stroller ramps, accessible public restrooms, easy access to schools and childcare centers, easy access to parks, and more.

Considering the Needs of all Generations

Building cities that foster independence among children and older adults through thoughtful planning and design helps to lessen the caretaking responsibilities that disproportionately fall to women.

Integrating Women’s Needs into Urban Spaces

Some cities have chosen to address these issues by creating women-only spaces, like women-only transit cars in Tokyo and Mexico City. While this might be a band-aid fix for a symptom, we must also tackle the underlying problem. A gender equitable approach is a holistic, integrated approach that helps to empower women to take up space and participate in public life in an equal way.

MKSK is invested in exploring best practices like these so that we can continue to plan and design a world in which we all want to live.

Sarah Lilly, AICP, is an Associate and Urban Planner with MKSK. She is passionate about fostering vibrant communities through meaningful planning processes and public engagement. Through her work, she strives to discover and celebrate the unique assets of each community or place for which she plans, crafting tailored policy and project recommendations that build on their authentic identity. This is reflected in her attention to high-quality graphics, plans, and deliverables. Sarah has a Master of City and Regional Planning from The Ohio State University and a dual Bachelor of Arts in Geography and Urban and Regional Planning from Miami University. She is actively involved in volunteer and outreach programs to advance the planning profession and foster the next generation of planners.

Sources:

Evenson, K. R., Cho, G. H., Rodríguez, D. A., & Cohen, D. A. (2018). Park use and physical activity among adolescent girls at two time points. Journal of sports sciences, 36(22), 2544–2550. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1469225

Fairchild, K., Rudman, L.A. (2008). Everyday Stranger Harassment and Women’s Objectification. Soc Just Res 21, 338–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-008-0073-0

Hayden, D. (1980). What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work. Signs, 5(3), S170–S187. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173814

Ison, J., Forsdike, K., Henry, N., Hooker, L., & Taft, A. (2023). "You're just constantly on alert": Women and Gender-Diverse People's Experiences of Sexual Violence on Public Transport. Journal of interpersonal violence, 38(21-22), 11617–11641. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605231186123

McGuckin, N., & Murakami, E. (1999). Examining Trip-Chaining Behavior: Comparison of Travel by Men and Women. Transportation Research Record, 1693(1), 79-85. https://doi.org/10.3141/1693-12

Kurshitashvili, N., Domínguez González, K., Mehmood Alam, M., González Carvajal, K., Pickup, L., Mancini, L., Shah, S., Mohankumar Jaya, V., & Rajiv, R. (2022). Integrating Gender Considerations into Public Transport Policies and Operations—Promising Practices. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Walker, S., & Clark, I. (2023). 2023 Research Report. Make Space for Girls. https://www.makespaceforgirls.co.uk/resources/research-report-2023