Doing Good: How Do We Design for Wellness?

By exploring landscape design through the lens of well-being, our work looks to solutions that promote restorative, supportive spaces.

As designers of the landscape, we have endless opportunities to shape people’s experience of outdoor space. Our work can focus on doing good for the communities we serve by addressing mental, social ,and physical wellness components. To promote wellbeing, we can set the stage for beneficial biophysical interactions (such as introducing trees in a city to clean the air before it reaches our lungs), cultural interactions (for example, creating a park where people can gather), and biotic interactions (for example, integrating nature play where children are exposed to immune-building beneficial bacteria). Every day, a growing body of research continues to find new connections for how human well-being is tied to the environment.

Adapted from Valentine Seymour. The Human-Nature Relationship and Its Impact on Health: A Critical Review. Frontiers in Public Health. 2016. Icons image: Flaticon

Well-being is shaped by biological, physical, and cultural interactions that designers enhance.

But how do we strategically shape these interactions using our architecture toolkit? Pulling from the framework developed by William Browning, Catherine Ryan and Joseph Clancy for Terrapin Bright Green in 2014, we deploy a set of design tools that fall into three inter-related strategies: nature in the space, natural analogues, and nature of the space.

Adapted from Valentine Seymour. The Human-Nature Relationship and Its Impact on Health: A Critical Review. Frontiers in Public Health. 2016. Icons image: Flaticon

Designers can manipulate interactions in the environment by tapping into three types of design strategies.

First, manipulating nature in space allows us to physically insert living systems and ecological processes into designed landscapes, when appropriate. This can be a green wall, a street tree, a pond or a simple design centering on temperature and light. Second, introducing natural analogues, such as patterns, textures, or arrangements that are found in living, geologic and hydrologic systems gives us another set of helpful tools, especially in more constrained urban environments. Third, designing the nature of the space by focusing on how volumes of space can influence how users of the landscape feel can make an immense difference in comfort and a sense of wellbeing. Within each strategy, specific patterns emerge.

Browning, Ryan and Clancy proposed 14 patterns of design that could be used by designers to improve well-being.

Here’s a look at how some of our projects in Washington, D.C. embrace some of the patterns of design for well-being.

THE APOLLO

Prospect: Spaces with prospect are associated with a comforting sense of control and safety, as well as freedom and openness. Prospect provides information and context, helping to reduce stress, especially in unfamiliar places. At The Apollo, the design team introduced large, linear seating steps to give residents and visitors of this multi-family building many opportunities to absorb the city’s skyline, urban grid, and national monuments.

Visual Connection with Nature: Introducing elements that convey a sense of time and connection to other living things has been linked to reducing stress, improving concentration, and stimulating positive emotional response. Surrounding the pool terrace of The Apollo, a multi-family building in a dense urban matrix, the design team introduced climbing vines and linear planters. These plantings link the communal rooftop with seasonality, growth and living systems.

DIAMOND TEAGUE PARK

Non-visual Connection with Nature: Being able to hear, touch, smell or taste living systems or natural processes can improve psychological restoration. At Diamond Teague, a riverfront park in southern Washington, the design team blurred the edges of the urban fabric where it meets the Anacostia River to enable people to hear birds, touch the water, and paddle off with kayaks to explore the river with all five senses.

Presence of Water: Looking at water is linked with stress reduction, improved concentration, and a lowered heart rate, among other studied benefits. Water is an element that stays fascinating despite repeated exposure. The design team has introduced large sinker log benches to invite visitors to sit and linger facing the river.

1101 K STREET

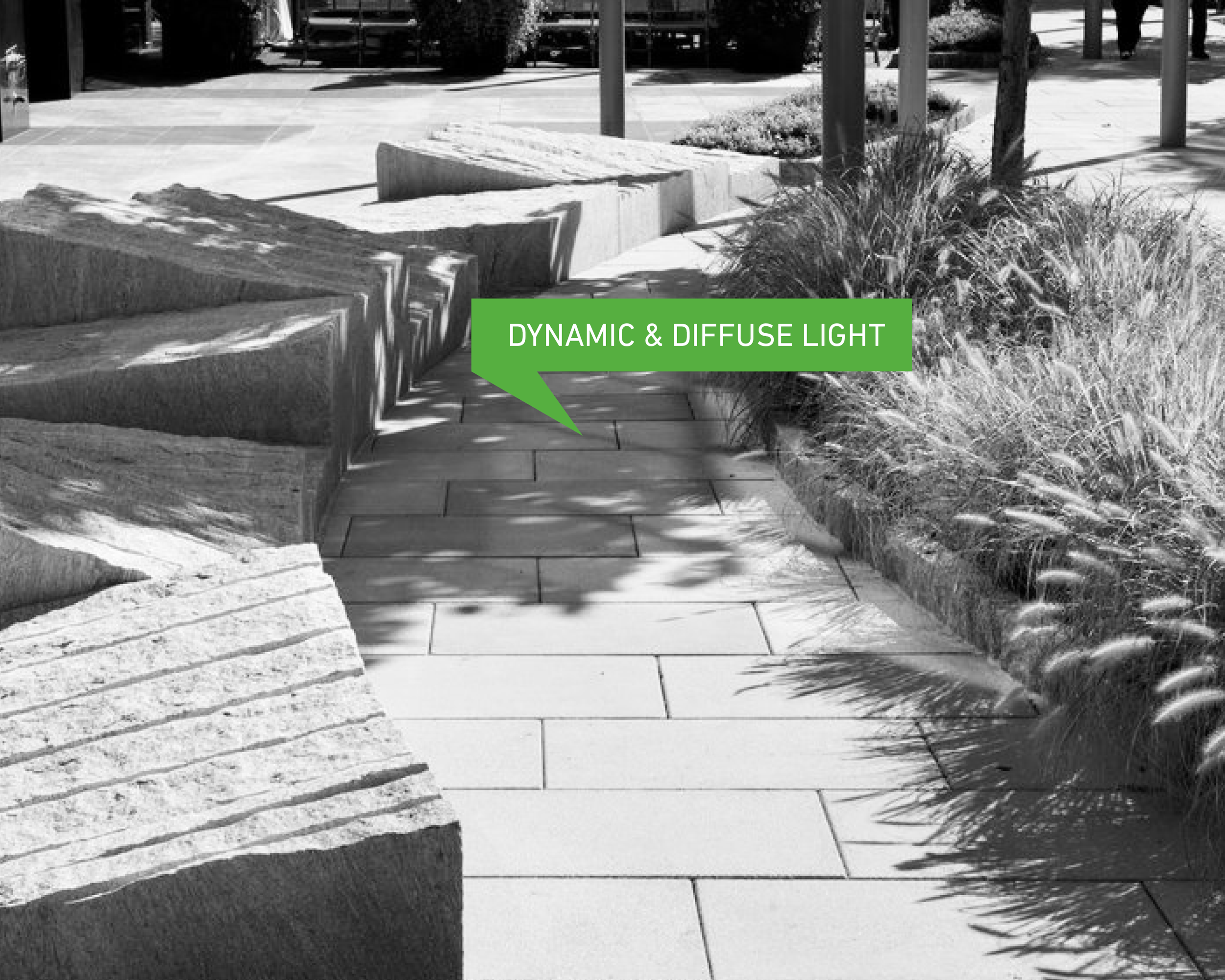

Material Connection with Nature: The opportunity to use colors and textures to influence feelings of comfort is growing as a field of research. At 1101 K Street, a 50-foot-wide pedestrian zone between the street and the adjacent buildings, the design team used an analog for a rocky outcrop, introducing geologic elements that inspire curiosity and hint at a bigger story. With minimal material processing, the stones are recognizable as rock but have a site-specific aesthetic that makes them feel relevant and coherent within the city’s streetscape.

Dynamic and Diffuse Light: Light and shadow can help to express the passing of time through days and seasons, as well as inspire a sense of soft attention. At 1101 K Street, swaying tree canopies and grasses provide constantly changing moments, while the linear light posts create shadows that grow and shorten with days and seasons.

Non-rhythmic Sensory Stimuli: Non-rhythmic patterns, those that are not easily predictable to an observer, have been linked with feelings of restoration. They allow for momentary distraction by providing stimulating but non-threatening information in the landscape. By selecting playful dancing grasses in the streetscape design, the team introduced gentle movement to an otherwise static landscape.

Together, these patterns of design help us explore where wellness benefits can be incorporated into site-specific, context-relevant design. The design tools are not prescriptive and aren’t meant to be used as a project checklist. Instead, we use them to inspire a lingering look on each element of our designs and ask ourselves whether the project could accommodate more meaningful elements or juxtapositions to strengthen our designs for the wellbeing of the communities we serve.

Gaëlle Gourmelon is an Associate at MKSK in Washington, DC. Through her training in public health, she researched how park use is linked to health outcomes. This work led her to pursue a master’s degree in landscape architecture to design places of well-being. She is deeply interested in the cultural understanding of the concept of nature and in its biological and psychological impacts.

SOURCES:

William Browning, Catherine Ryan and Joseph Clancy. "14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health & Well-being in the Built Environment," 2014, Terrapin Bright Green LLC

Valentine Seymour. "The Human-Nature Relationship and Its Impact on Health: A Critical Review." Frontiers in Public Health. 2016.