Can Today’s Slow Street Pave the Way for The City We Need?

A COVID-19 Design Retrospective

As we turn the corner to Spring, we mark three years since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The disruption to daily routines caused by the global crisis created hardship and anxiety, but it has also presented us with the unique opportunity to reevaluate what we prioritize in our lives, and how we use and allocate important physical resources.

From streateries and parklets to Slow Streets, the global pandemic heightened our appreciation of public space and redefined our understanding of what a park can be. Over the past few years, cities and communities all over the world have actively reimagined the everyday use of public spaces, using streets and streetscapes for health and wellness practices, recreation, socialization, expression, and more.

Public spaces, from our largest city parks to the refuge of an open bench, have always been critical havens for mental and physical wellness. Our bike lanes, waterfront parks, and urban trails have provided venues for exercise, release, and contemplation. During the pandemic, these spaces became especially important for city dwellers looking for decompression after a hectic day living, working, and even schooling within the same confined space. Unsurprisingly, a growing body of scientific evidence confirms that spending time outdoors and in green spaces confers significant health benefits – reduced stress, better concentration, and lower blood pressure to name a few. As we look back to an inflection point, we find ourselves living through a separate but related crisis; as urban areas have densified, our cities have failed to address the growing need for outdoor space that is accessible, flexible, and serves the needs of our communities.

Fortunately, we’re better equipped than ever to rethink the public realm in order to provide valuable open space where, and when, it is needed most. Cities and suburbs around the world seized the moment to reclaim underutilized spaces in order to provide much-needed capacity to protect and enhance the lives of urban dwellers. Permits expanded pedestrian right-of-ways, creating additional space for exercise and recreation. Parklets and streateries transformed streets into vibrant, activated, and occupiable streetscapes. Community-led efforts, such as Porchfest in Washington, DC’s Petworth neighborhood, explored the possibility of offering a new venue for cultural expression. These everyday interventions and improvisations allowed residents to transform existing infrastructure into localized park space that meets a diverse range of needs.

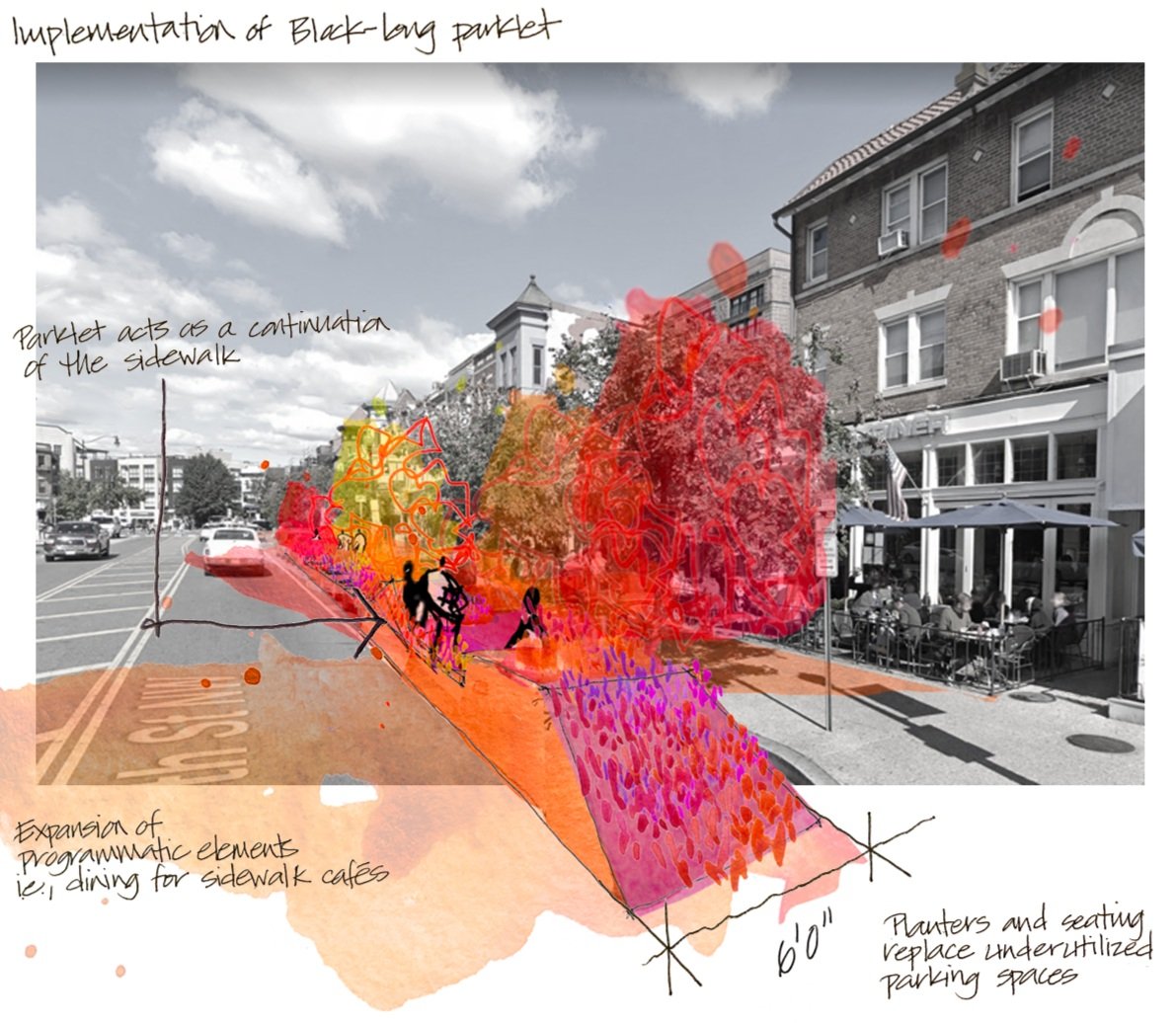

The integration of a block-long parklet safely expands pedestrian-occupied space, adding additional seating and planting to the streetscape.

The movement known as “Slow Streets” – closing roads to vehicular traffic, widening sidewalks, and similar measures that expand the reservoir of available public space for pedestrians – is already being deployed around our city to alleviate crowded sidewalks, provide space for queueing outside of grocery stores, and open up underutilized roads for safe, socially-distanced recreational use.

The idea of temporarily appropriating or repurposing public space is not entirely new. Tactical Urbanism, a practice popularized in the late 90’s, is an approach to urban space-making that circumvents costly and slow institutional processes in favor of rapidly-deployable plans of action. The approach focuses on collaborative and adaptable measures, participatory actions, and affordable materials in order to test new uses for urban space in real time. Food trucks, parklets, pop-up plazas, and little libraries are a few well-known manifestations of Tactical Urbanism that have made immediate and meaningful contributions to cities around the world.

While adopting these methods to enact critical public health measures during the COVID-19 crisis deemed appropriate, public officials and designers of the built environment must go further. The history of Tactical Urbanism tells us that the simple act of providing public access to otherwise unusable spaces or resources can be transformative and, when it resonates with local communities, will generate grassroots political support for making such changes permanent.

With this in mind, the actions that we enacted to combat the spread of the Coronavirus take on a new meaning moving forward. The repurposing of parking spaces in order to widen sidewalks, for instance, could ultimately pave the way to provide more permanent outdoor dining space for restaurants and cafes. One can imagine that reclaimed parking spaces could be reborn as block-long parklets that help calm busy streets, offer space for flexible programming, provide more native vegetation for urban pollinators, and yield memorable and dynamic streetscapes.

Larger interventions, such as temporarily converting roads into pedestrian promenades suggest the potential for a whole new class of linear parks that could one day help address inequities related to how public spaces are distributed throughout the city. Once we start to think big, why not dare to imagine DC’s Whitehurst Freeway or Suitland Parkway repurposed as temporary promenades today, perhaps laying the groundwork for exceptional public spaces in the future?

A concept sketch reimagines DC’s Whitehurst Freeway as a mixed-use trail and public space.

We are in the midst of a once-in-a-generation inflection point in the history of our cities and the impact of decisions we make about public space today may well shape the places we live for years to come. The rewards for taking decisive action, and thinking big, have the potential to be transformative.