Downtown Columbus Strategic Plan

Downtown Columbus Strategic Plan

Moline Riverfront + Centre Plan

One Health District Master Plan

Inner Loop North Mobility & Development Strategy

Chattanooga Riverfront District Plan

Downtown Toledo Master Plan

Eastland for Everyone Plan

Reedy River Redevelopment Area and Unity Park

Lakeview Roscoe Village Master Plan

Engage New Albany Strategic Plan

Decatur Town Center Plan 2.0

Birmingham Northwest Downtown Development Plan

Cleveland Cuyahoga Riverfront Master Plan

Sewall's Island and Factory Square Redevelopment Plan

Downtown Gainesville Strategic Plan

Town of Hilton Head Island Housing Framework

CONEA Upper Falls Neighborhood Master Plan

Northwest Indiana Transit Development District Planning

Gary Metro Station and Downtown TOD Visioning

Memphis Innovation Corridor Transit Oriented Development Plan

Akron TOD Feasibility Study

LinkUS Northwest Corridor Mobility Study Development Framework

Bike New Albany Plan

Walnut Hills Reinvestment Plan

Southwest & Buzzard Point Flood Resilience Master Plan

Tysons Placemaking Vision and Framework Plan

Clark Street Crossroads

Downtown Columbia Strategic Plan & Design Guidelines

Akron Neighborhood Plans

Skokie Main Street Corridor Vision

Greencastle-DePauw Master Plan

Akron Downtown Vision & Redevelopment Plan

Atlanta Upper Westside Community Improvement District Master Plan

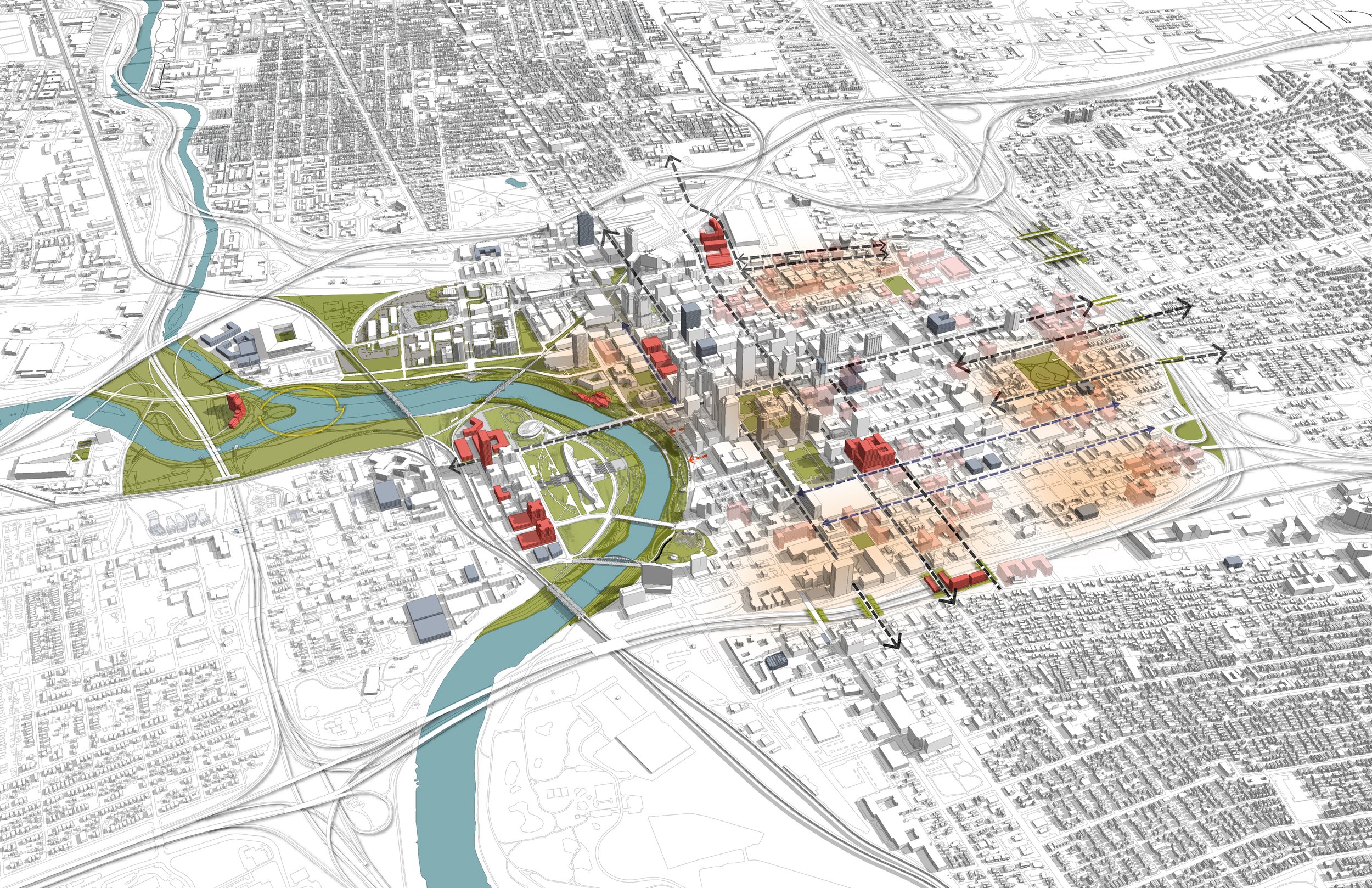

Tulsa Arena District Master Plan

Oxford Tomorrow Comprehensive Plan

LEAP Lebanon Innovation District

Bonanza Park & Snow Creek Area Plan

Woodbridge Neighborhood Development and Design Guidelines

Noblesville East and West Gateways

Arena District

Bridge Street District

Van Aken District

Scioto Greenways

Unity Park

Promenade Park

University of Cincinnati Library Square Renovation

Lawrenceburg Civic Park

McFerson Commons

District Wharf Promenade

District Wharf Fish Market

Dorrian Green

Grandview Yard

Easton Urban District

ScottsMiracle-Gro Field

Preston Centre

The Ohio State University Mirror Lake

Ballston Quarter Origin

Ballston Quarter Mall

Cincinnati Open

Rise on Chauncey

The Apollo

Crocker Park

Audi Field - Parcel B

Liberty Center

The Edison at Union Market

Astor Park

Purdue University Stormwater + Open Space Study

Purdue University Giant Leaps Master Plan

Michael B. Coleman Government Center and Municipal Campus

ReWa Innovation Campus Vision Plan

The Ohio State University Carmenton Design Guidelines

Garrison Elementary School

University of Cincinnati Clifton Court Hall

The Ohio State University North Residential District Transformation

Corwell Health CTI Campus

The Ohio State University Framework Plan 3.0

Cornerstone University Master Plan

University of Louisville Belknap Village North & South Residence Halls

Xavier University Alter Hall and Xavier Yard Transformation

Winthrop Family Historical Garden

Long Street Bridge and Cultural Wall

Evanston Environmental Equity Investigation

Kentucky State Capitol

Southwest Neighborhood Library & Park

Columbus Museum of Art Expansion

Franklin Park Conservatory North Star Master Plan

Peace Center Campus Plan

Conner Prairie Interactive History Museum

Livingston Park Cultural Panels

Louisville Northeast Regional Library

The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

Nationwide Children's Hospital

Norton Healthcare Sports & Learning Center

Cincinnati Children's Hospital Clinical Sciences Pavilion

Chlois G. Ingram Spirit of Women Park

White River State Park Extension

Louisville Waterfront Park Phase 4

PlayPort at Waterfront Park

Summit Park

Scioto Audubon Metro Park

Bowling Green Riverfront Park

Rose Run Corridor

Canton Parks Improvement Plan

Riverside Crossing Park

Aurora Park

Great Parks of Hamilton County Comprehensive Plan

Great Parks of Hamilton County Sharon Centre Playground

Cason Family Park

Indian Springs Environmental Discovery Center

Blanton's Landing Feasibility Study

Grange Insurance Audubon Center

Cleveland Park Master Plan

Rocky Branch Greenway

West Louisville Outdoor Recreation Initiative

Marcum Park

Cleveland Cuyahoga Riverfront Phase 1

The Capital Line

The Peninsula Public-Private Streets

Buffalo Riverline Trail

State Street Master Plan and Implementation

I-70/I-71 Innerbelt Design Enhancement

Centennial Plaza

Indiana Statehouse Bicentennial Plaza

Ludlow Alley

Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park

Diamond Teague Park

Cady's Alley

Columbus Convention Center Expansion and Streetscape

Silver Spring Metro Plaza

Centennial Commons

Creative Campus Streetscape

Short North Streetscape Improvements

Van Andel Arena Plaza and Alley

Morgan Square Enhancement Plan

Imagination Alley

Oak Street Corridor Safety Enhancement Plan